Social work can be seen as an endeavour of attempting to grasp at another person’s reality. We assess people and families striving to be as faithful as possible. In this article I will discuss how Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein may assist in providing some warnings and possibly a map of where the limits lie in attempting to describe another human’s existence.

Wittgenstein is often seen as a totally impenetrable and unnecessarily difficult thinker, whose tomes are the jealous property of grey faced professors at posh Universities. I aim to hopefully present some straightforward uses for his philosophy on language and how it can help social work practice.

Life and Times

Wittgenstein’s life story would not fit into one film! Don’t believe me? Here goes!

He was born into a large super wealthy Jewish family in Austria with their wealth matched only by the Rothschild’s (them of the Illuminati). He went to primary school with Adolf Hitler. As a toddler he made machines out of scrap discarded items in his home, he designed a new method to heal wounds after car accidents, he invented the corner radiator, created a precursor to the jet engine and liked a pint round Jesmond when working in the RVI. Despite this list he was the least famous member of his family. One his brothers was the best concert pianist in the world which he did playing only with one hand (strangely there is an episode of MASH based on his life).

Despite his wealth he left the 7 palaces and even more grand pianos (his siblings had one each) and served in the first World War with him single handily diverting machine gun fire on the Russian front and being awarded medals for bravery. During this time on one of the most brutal campaigns in WW1 he wrote one of the greatest works of philosophy the Tractatus.

However the true genius of Wittgenstein is that he is two philosophers in one as his later work comes to re-meet and reinvent (or more accurately decimate) his earlier work, with this hinging on language being variously limited, meaningless and redundant.

Language according to Wittgenstein is best seen, and perhaps can only be seen, in the context of a game, with a game being described as an activity where participants have a pre-understanding of some commonly held rules. The important point here is the meaning is held only between the active participants. To an outsider it is meaningless.

This chimes exactly with a recent Radio 4 documentary about a young parent’s experiences of the family court where their children are removed. One quote in particular about the barristers and the social worker struck me – “it was like a play where everyone but me had a script and knew their lines but me(sic)”.

This highlights a true Kafkaesque nightmare. This parent does not understand the very language that is being used to deny her of her most basic right to be a mother to her child. How do we, in the most caring of professions, engage in such a cruel language game?

It is highly likely that the barrister, the judge and the solicitors have never seen one second of the parent being a parent yet they are able to make complex arguments, statements and decisions on that very matter. Their Jargon is as removed from the reality as their experience is. The below attempts to formalise this picture.

This frames language as being the main agent of oppressive practice. Power is held by those whose professional and remote jargon trumps real experience every single time. This reminds me of an old thought I had at my first Section 47 strategy meeting when I realised (despite being a newly qualified worker), I was the only person in the room to have seen the family, but everyone else’s perception held much more sway and influence. What a strange set of affairs! It’s all a bit like reviewing a film without seeing it. At best you will only offer a derivative generic version of what’s come before, which is shorthand for terrible social work practice, “I don’t need to visit the family I have worked with neglect etc for over twenty years” is surely the defence of the team manager. Do we overvalue an argument from career experience at the expense of the view from the practitioner who has seen the “whites of the family’s eyes” and visited their home? If good social work aims to get to the essence or the true nature of a child and their family’s life this cannot be done from a remote place. You’ve got to be sat at the board to play the game.

Wittgenstein provides a good example that chimes well with social workers, that of the family resemblance. Look at the family picture below:

It is clear that they are all related and resemble each other; however their quality cannot be pinned down to a few simple elements. It is a collective range of positive and negative features that create a very real but fuzzy concept. This feels familiar. As social workers we often have to describe things like the mood in the house or the relationship between individuals, how close are we getting to the real picture, especially when we only demonstrate our evidence through written assessments.

Indeed, as social workers we must be cautious that whilst we strive to understand the context of the child and the parent, our language can only grasp at their reality fleetingly. To say we have fully captured (the language of a bounty hunter??) the child in our assessment is to crush their experience into oblivion. ‘I know better than you about your own experience’, is a disturbing thought in the extreme. Conceptually this can be seen as Naïve Realism (see poster). My world view is the solely correct one.

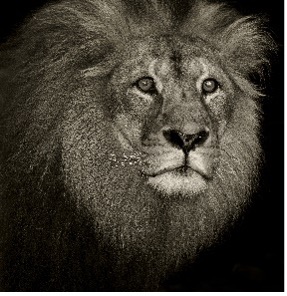

I’ll close on one of Wittgenstein’s most famous quotes, “If a Lion could talk, we could not understand him”

The message here hinges on a double meaning of understanding. Whilst we could understand the grammar, words and sentences if the lion spoke perfect English all of the common concepts would not be shared ones. Their lives as a lions are inaccessible to ours as humans with no common rules for the exchange.

Luckily as social workers we do not have such a chasm to cross, however, we must acknowledge there remains differences and fuzziness that cannot be fully held by our assessment and certainly cannot be got at remotely by professionals who have never met the family. So, tread carefully, meet families where they are (actually and figuratively) and be cautious of language’s exclusory and assumptive power.

You might also like the following from George and the Social Work Shorts Team talking more about Wittengstein’s Lion

George talks about Poverty in this Social Work Shorts Podcast

Or listen to George talk to Stephen about Risk

About the writer…..

George Bull

George has been a social worker for 10 years working mainly in child protection and Early Help. He has lectured with Jamie Scorer at New College Durham, University of Sunderland and University of Northumbria in solution focused practice.